Volume 48 - Issue 3

Is the One God of the Old Testament and Judaism Exactly the Same God as the Trinitarian God—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit—of the New Testament and Christian Creeds?

By John Jefferson DavisAbstract

This article argues that the One God of the Old Testament and Judaism is exactly the same God as the Trinitarian God of the New Testament and Christian creeds. The standpoint presupposed is that of the orthodox biblical teachings on the Trinity expressed in the Nicene and Athanasian creeds. The paper presents new arguments supporting the unity and coherence of Old and New Testament revelation, employing (1) new analogies from modern physics, and (2) new philosophical insights concerning the properties of objects nested in a larger whole, and how those objects are to be properly counted in relation to the larger whole.

Modern Old Testament scholarship has increasingly recognized and documented the uniqueness of Israel’s monotheism—the one true God of Old Testament revelation—against the background of the polytheistic religions of the Ancient Near East.1 During this same period, the renaissance of interest in the doctrine of the Trinity since the seminal work of Karl Barth and Karl Rahner, has caused Christian theologians and philosophers of religion to wrestle more deeply with the distinctive claims of ecumenical creeds such as the Athanasian Creed, which assert that “the Father is God, the Son is God, and the Holy Spirit is God, and yet there are not three Gods, but only one God.”2 How can it be logically and theologically coherent to affirm both that Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are each fully and equally God, and yet there be only one true God?

It is the purpose of this paper to argue for an affirmative answer to the question posed in the paper’s title: “Is the One God of the Old Testament and Judaism Exactly the Same God as the Trinitarian God—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit—of the New Testament and Christian Creeds?” Alternatively, the question could be stated, “Is the Yahweh who spoke to Moses from the burning bush exactly the same God later revealed as the Father of Jesus Christ, the eternal Logos and Son of God, and the Holy Spirit?”

It is not the purpose of this paper to discuss recent controversies on the Trinity, either, for example, as to whether so-called social models of the Trinity can be used to support certain social and political agendas; or, whether a supposed “eternal subordination of the Son” supports male headship in the family and the church. The standpoint presupposed in this paper is that of historic Trinitarian orthodoxy as held by the Cappadocian fathers of the East and the Latin fathers of the West, and expressed in the historic Nicene and Athanasian creeds: three distinct, coeternal and fully coequal Persons—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit—subsisting in one undivided divine substance, equal in power, substance, and glory.3

The paper will present new arguments supporting the unity and coherence of Old and New Testament revelations concerning the nature of God, using new analogies from modern physics (the principle of wave-particle complementarity; the structure of the proton constituted by three quarks), and new philosophical insights concerning the properties of objects nested in a larger whole (e.g., three distinct branches of government contained in the larger whole of one federal government; two identical twins nested in the womb of one pregnant woman; the human nature of Jesus nested or contained within the divine nature of the Logos and eternal Son), and how those objects are to be properly counted in relation to the larger whole.4

By way of introduction, biblical and theological justifications need to be offered for the use of analogies from the natural world for the Trinity.5 The idea that vestiges of the Trinity (vestigium trinitatis) could be discerned in the natural order is an ancient Christian belief, being found in the church fathers. In book six of his treatise on the Trinity, Augustine stated:

So, then, as we direct our gaze at the creator by understanding the things that are made [Rom 1:20], we should understand him as a triad, whose traces [vestigium] appear in creation in a way that is fitting.6

Augustine found traces of the Trinity in the psychological powers of the human soul, e.g., being, knowing, willing; memory, understanding, and will; lover, the beloved, and their mutual love.7 Prior to Augustine, Tertullian had found in the natural order several images of God’s triadic nature: root, tree, and fruit; fountain, river, and stream; sun, sun’s ray, and the highest point of the ray.8 Other popular illustrations have included ice, water, and steam; the three dimensions of space; past, present, and future; egg shell, egg white, and egg yolk; a three-leaf clover, and so forth. Gregory of Nazianzus used a famous illustration of light from three superimposed suns:

We have one God because there is a single Godhead. Though there are three objects of belief [Father, Son, Spirit].… They are not sundered in will or divided in power…. It is as if there was a single intermingling of light, which existed in three mutually connected suns.9

Martin Luther believed that “in all creatures there is and may be seen an intimation of the Holy Trinity,” citing examples from sun, water, and plants. “God is present in all creatures, even in the tiniest leaf and poppy seedlet.”10

These church fathers and later Christian writers saw biblical justification for such comparisons, especially in Paul’s statement in Romans 1:19–20:

What may be known about God (τὸ γνωστὸν τοῦ θεοῦ) is plain to them [the Gentiles], because God has made it plain (ἐφανέρωσεν) to them. For since the creation of the world God’s invisible qualities (τὰ … ἀόρατα αὐτοῦ)—his eternal power (ἀΐδιος αὐτοῦ δύναμις) and divine nature (θειότης)11 have been clearly seen (καθορᾶται), being understood (νοούμενα) from what has been made, so that men are without excuse.

Paul is not asserting what in later Western theology from the thirteenth century came to be known as “natural theology.” Paul is not teaching that unaided human reason, examining the features of the natural world, can know that there is a wise, powerful, and benevolent deity (though this is in fact the case). The starting point is God’s revelation—what God has made plain (ἐφανέρωσεν). Human reason is the receptive instrument, not the ground and foundation of proper knowledge of God.12

In his second missionary journey, Paul declared to his Gentile listeners in Iconium and Derbe (Acts 14:15, 17) that the God who

made heaven and earth and everything in them (πάντα τὰ ἐν αὐτοῖς) has not left himself without testimony: He has shown kindness by giving you rain from heaven and crops in their seasons: he provides you with plenty of food and fills your hearts with joy.

The kindness and generosity of the one true God, the God of Israel, is demonstrated in the regularity of seasons and weather that provides humanity with food and enjoyment. Such a view of God’s general revelation in nature was not original with Paul, of course. He stood in the ancient tradition of Israel’s wisdom literature, reflected in texts such as Psalm 19:1 (“the heavens declare the glory of God”), or Proverbs 8:27, 30, where the personified Wisdom declares that “I was there when he set the heavens in place.… Then I was the craftsman at his side.” The fingerprints of Wisdom, so to speak, have left their traces on the things God has made.13

Admittedly, these biblical texts do not speak explicitly of God’s triune nature being revealed in the natural order. Nevertheless, they do teach that some partial yet true knowledge of the true God can be discerned. In the later history of redemption—after Christ and the Spirit have been more fully revealed, it was to be expected that New Covenant believers would look for such hints of the Trinity.

A further caveat is in order before addressing the main topic of this paper—the thesis that the one God of the Old Testament is the same God as the Trinitarian God of the New Testament. The church fathers and later commentators have recognized that no analogy from the created order can be fully adequate for understanding the nature of the Triune God. The infinite God cannot be contained or circumscribed by any finite entity or concept. Furthermore, Christian theologians have long recognized that such illustrations of the Trinity from the natural order can, taken in isolation and apart from the canonical teachings of Scripture, seem to better illustrate the heresies of tritheism, modalism, or subordinationism than the church doctrine of the Trinity.

In his discussion of the persons of the Trinity, Augustine famously said that he made his proposals “not in order to give a complete explanation of it, but that we might not be obliged to remain silent.”14 The current proposal is being made in the same spirit.

1. The Proper Counting of Objects Nested in a Larger Whole

This section of the paper explains and illustrates a Nested Counting Rule (NCR), a rule for properly counting objects that are nested or contained in a larger whole. Several examples could be considered: two identical twins nested within the womb of a pregnant woman sitting in the doctor’s waiting room; three branches of government (executive, legislative, judicial) nested within one federal government; the human nature of Jesus nested within the divine nature of the Logos and eternal Son; the three Person of the Trinity (Father, Son, Holy Spirit) nested within the one divine nature equally shared by all three.

In a nested relation, the objects that are nested within a larger whole are not merely contained in something larger in an accidental or temporary manner, but are organically and more integrally connected to the larger, containing whole. For example, if I carry my pet cat Ginger to the vet in a carrying cage, Ginger is spatially contained or “nested” (in a weaker sense), but this containment is only temporary and accidental. Ginger is not essential to the identity of the cage, and the cage is not essential or integral to the identity of Ginger. On the other hand, the human nature of Jesus was (and still is) truly nested or contained within the Logos. The Logos is essential to the true identity of Jesus. The Jesus of the Gospels is not just any “Jesus”—whether the Jesus of Dan Brown and the Da Vinci Code or of the gnostic Gospel of Thomas, or even the Jesus as understood today by Orthodox Jews, but the Jesus of Nazareth who was truly and fully indwelt by the Logos, the eternal Son and second person of the Trinity. Likewise, the Word who became flesh is not the impersonal Logos of Stoicism or Tao of Taoism, but the personal Word, the second person of the eternal Trinity who truly dwelt in the body of Jesus (John 1:14; cf. Col 2:9).

In a true nested relation, the relation between the nested objects and the larger, nested whole is one of reciprocal identity conferral. The identity of the whole is connected to the identity of the parts, and the identity of the parts is integrally connected to the identity of the whole.

The Nested Counting Rule will be stated in two forms, the first (NCR1) informal, and the second (NCR2) more detailed and technical.15 The rule will then be applied to three examples: (1) three branches of government in the American federal government; (2) the mystical union of Jesus and the Logos in the incarnation to constitute Jesus as the Mediator and God-Man; and (3) Father, Son, and Holy Spirit nested in the one undivided divine essence to constitute the Trinity.

NCR1: Two or more parts connected in a nested relation constitute an integrated whole that is properly counted as numerically one.

NCR2: In a whole-part relation in which n parts are nested in a larger whole (where n is a whole number), the whole and the parts are separately counted, such that the whole so constituted (N, the “Nester”) is properly counted as one (N = 1), while the constituent parts (n1, n2, n3 … nn , the “nested”) are properly counted as n.

First, consider the example the American federal government, containing and constituted by the three branches: the executive, the legislative, and the judicial. Each branch is considered to be co-equal in authority, and distinct (though neither autonomous nor disconnected) from the others. The branches (“parts”) are nested within a larger whole, the federal government. The parts are properly counted as three, while the larger whole—the American federal government, is properly counted as one. There are three branches of government, not one; and there is one federal government, not three. The parts and the whole are counted separately, not summatively, such that it is not the case that there are either four parts of government or four whole federal governments.

Second, in the case of the incarnation and hypostatic union, the divine Person of the Logos creates and is united with (from the first instant of conception) the fully human Jesus, so as to constitute the one Mediator, the God-Man, Jesus Christ.16 There is only one God-Man, only one Christ, not two Christs or two God-Men. The two constituting individuals, divine and human, can be distinguished but not separated or divided, and so the integrated whole so constituted is properly counted as one. There are two individuals in a nested relation —Jesus and the Logos—and one and only one whole: the Christ, the God-Man.

The concept of a nested relation has not been extensively developed in the field of mereology, in either the modern or pre-modern periods.17 However, we can recognize that the notion of one thing being contained in another is found in patristic discussions of the Trinity. Augustine had stated that with respect to the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, “one is as much as the three together … each are in each, and all in each, and each in all.”18 For Hilary, the persons of the Trinity “reciprocally contain one another, so that one should permanently envelop, and also be permanently enveloped by the other.”19 John of Damascus spoke of the persons “abiding and resting in one another,” inasmuch as “the Son is in the Father and the Spirit, and the Spirit is in the Father and the Son, and the Father is in the Son and the Spirit.”20 While these patristic authors do not employ the technical terminology of nested relation, the basic concept of one thing containing another is clearly present.

When applied to the Trinity, the Nested Counting Rule allows us to recognize Father, Son, and Holy Spirit as numerically three persons, co-equal and co-eternal instantiations of the one undivided divine essence. At the same time, as a consequence of their reciprocal nesting, they jointly constitute the one true Triune God. There is one and only one Triune God, not two or three or more triune gods. The Trinity is properly countable as one inasmuch as the constituting persons of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, though distinguishable, cannot be separated or partitioned, remaining necessarily, reciprocally, fully, and congruently nested in one another and in the one and the same divine essence to constitute the one Triune God.

The Trinity, the fullest and most explicit identity concept for the Christian God—the “Nester” in this case—is properly counted as one. There is only one God, not three Gods; only one Trinity, not three Trinities; only three persons, not four persons. Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are the three distinct, co-equal and co-eternal persons nested within the one Trinity and one divine essence. Nester (God; the Trinity) and the nested (Father, Son, Holy Spirit) are counted separately, not summatively.

God = Trinity = 1;

Father, Son, Holy Spirit = Persons = 3.

When the Athanasian Creed states that “the Father is God, the Son is God, and the Holy Spirit is God”—and yet there are not three Gods—the copulative “is” should be taken not as a statement of strict identity, but rather as a statement of predication.21 Each person of the Trinity is fully and completely of the nature of God, i.e., fully instantiating the one divine substance shared by all three. Each of the three persons is wholly of the nature of God, but any one person is not identical to the whole of God.22 The one and only “whole” God is identical only to the one divine substance fully and equally instantiated, necessarily, eternally, and simultaneously by all three persons, Father, Son and Holy Spirit (n1, n2, n3 = 3) reciprocally and congruently nested in the one and only one God and divine nature (N = 1).

2. Analogies from Modern Physics: One Proton, Three Quarks and Complementarity

An important perspective on the one and threeness problem is provided by this analogy from modern physics: the proton constituted by three quarks.23 The existence of quarks was first hypothesized by the physicists Murray Gell-Mann and George Zweig in 1964, and then later confirmed in 1968 by experiments at the Stanford Linear Accelerator in California.24 The whimsical name “quark” was chosen by Gell-Mann after a perusal of James Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake, with its phrase “Three quarks for Muster Mark.”25 According to Gell-Mann, the number three fitted perfectly with the way quarks occur in nature.

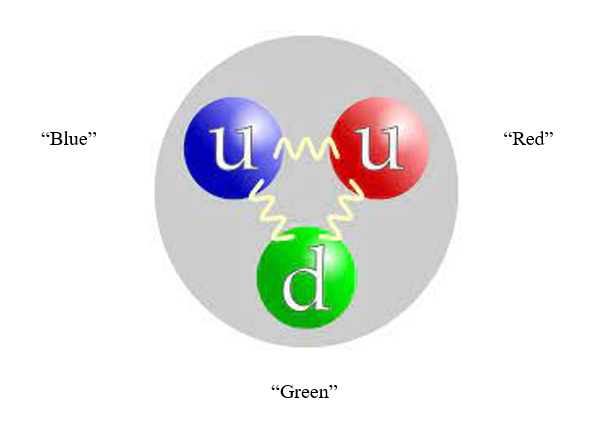

Heretofore, the proton had been considered (along with the neutron) the fundamental particle of the atomic nucleus. The name “proton,” meaning “first” in Greek, had been given to it by the English physicist Ernest Rutherford in 1920 after his experiments on the hydrogen nucleus.26 In the current Standard Model of particle physics, the proton is now understood to be composed of three quarks tightly bound together by the strong nuclear force—two up quarks (u), and one down quark (d), as in the diagram below:

The quarks are so tightly bound together that they never appear in isolation in nature. The three quarks have the properties of mass, energy, electrical charge, and spin, properties shared by the proton which they constitute. But in addition, they have a distinctive quantum mechanical property known as “color charge,” a property which does not characterize the proton. The “colors” (red, green, blue) of the quarks are arbitrary and have no connection to the colors of light as we experience them. The colors of the quark, however, are intrinsic properties that serve to distinguish one quark from the others.

When interacting to form the one proton, the color charges of the three quarks are not conserved, such that the proton has no “color.” The distinctive color charges of the three quarks are ontologically present in the one proton, but phenomenologically absent, so to speak. Color is not attributed to the proton, even though it is a distinguishing property of the constituent quarks.

This “disappearance” or non-appearance of the color of the quarks in the proton is an example of another aspect of the nested relation, viz. the Non-Attribution of Distinctive Properties (NADP). This aspect means that when one or more objects are nested within a larger whole, one or more of the distinctive properties of the nested objects may not be necessary to the identity of the larger nesting whole. Those properties may be ontologically present in the larger whole, but not phenomenologically apparent. For example, consider a pregnant mother, Mary, carrying two identical twins in her womb at seven months gestational age. Mary is the only pregnant woman in the doctor’s waiting area at this time. In order for the doctor’s administrative assistant to pick out Mary from other (non-pregnant) women in the waiting area, it is not necessary for the assistant to know the gender of the twins, or their weight, color of eyes, etc. Those properties are ontologically present, but not phenomenologically apparent. It is apparent that Mary is pregnant, and the description “Mary, the woman who is seventh months pregnant” is sufficient to identify her.

In the case of the proton, the proton’s electric charge, mass, and spin are the properties that are sufficient to identify the proton as a proton (rather than as a neutron or electron). The “color” of the quarks is ontologically present within the proton, but is neither phenomenologically apparent nor epistemically necessary to identify the proton as a proton.

Now consider the case of Yahweh speaking to Moses from the midst of the burning bush. From the perspective of the New Testament and Christian faith, we believe that the Trinity was present in the burning bush. “Yahweh” and the “Trinity” are words that have different senses or connotations, but they have the same ontological reference: the one true God of Israel, the Creator and Judge of all things. The distinctive personal marks of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, the three Persons of the Trinity, were ontologically present, but were (like the colors of the quarks) at that time not phenomenologically apparent. At that stage of redemptive history, it was necessary for the oneness of God, of Yahweh, to be apparent—not the triune inner complexity of God’s being. Just as the proton has aspects of both oneness and threeness, so God has aspects of both oneness and threeness, but in neither case is it necessary for both oneness and threeness to be equally apparent at the same time and in the same context of redemptive history or experimental observation.

The principle of wave/particle complementarity in modern physics27 can provide another analogy relevant to the oneness and threeness problem of the Trinity. As the electron passes through a screen with two slits, it exhibits the properties of a wave. When the electron strikes the detector behind the screen, it impacts a definite location, and exhibits the properties of a particle. Although “wave” and “particle” have different senses and evoke different mental images, both have the same reference: the electron in the experiment. “Wave” and “particle” are complementary, not contradictory, ways of conceptualizing the electron. Both are legitimate categories, given the particular context in which they are used. In similar fashion, we can recognize that Yahweh, the one God of Israel that Moses encountered at the burning bush (Exod 3:1–6), is in fact the same Triune God revealed as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit at the baptism of Jesus in the Jordan River (Luke 3:21–22). God was revealed as one in the Old Covenant, and as three in the New. God can be recognized as both one and three, depending on the context of revelation.

From one point of view—that of ordinary chemistry and the periodic chart of the elements, the proton is one stable and indivisible particle. From the point of view of the Standard Model of particle physics, the proton is three quarks tightly bound by the strong nuclear force. Both descriptions are true and complementary, being relative to the context and purpose of the speakers. Similarly, both the “oneness” of Yahweh and “threeness” of the Trinity are truly predicated of the Christian God, in their respective contexts and purposes. They are complementary descriptions of the same God.

3. Summary and Conclusion

This article has argued that the answer to the question “Is the one God of the Old Testament and Judaism exactly the same God as the Trinitarian God—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit—of the New Testament and Christian creeds” is definitely and confidently “Yes.” New arguments and analogies in support of the logical and theological coherence of Old and New Testament revelation were drawn from modern physics and philosophy. The concept of wave-particle complementarity in physics was applied to the structure of the proton, i.e., one proton constituted by three quarks. Both statement are true: the proton can be viewed as one particle; the proton can be viewed as three quarks. The aspects of oneness and threeness are complementary aspects of the same particle, viewed from different frames of reference. Analogously, the Triune God can be conceptualized from the distinctive but complementary perspectives of oneness of essence and threeness of Persons. In both cases, neither oneness nor threeness are in themselves complete descriptions of the object in question, and yet both are essential for a more conceptually adequate understanding.

The Nested Counting Rule (NCR) for properly counting the components of a larger whole containing parts nested within it was illustrated and applied to the Trinity. Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, the divine persons nested within the one divine nature are properly counted as three, whereas the one divine nature nesting them is properly counted as one: one and only one divine essence; one and only one true God. There is only one true God, not three; there are truly three and only three divine persons, not four persons or four gods. The one God Yahweh of the Old Testament is the same God as the Triune God of the New Testament, revealed in complementary and not contradictory fashion, in the different contexts and circumstances of Old and New Testament redemptive history.

[1] See, for example, John H. Walton and Andrew E. Hill, Old Testament Today: A Journey from Ancient Context to Contemporary Relevance, 2nd ed. (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2013), pp. 110–16, “Contrast: Religious Beliefs in the Ancient World.” Walton and Hill compare and contrast Israel’s understanding of God with the polytheistic religions of the Ancient Near East in six areas: ultimate power; manifestations of deity; dispositions of the deity; autonomy of the deity; requirements of the deity; and human responses to the deity. From the perspective of systematic theology, see Fred Sanders, The Triune God (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2016), pp. 212–14, “The Trinity in the Old Testament.”

[2] For a survey of developments in modern Trinitarian theology, see Fred Sanders, “The Trinity,” in The Oxford Handbook of Systematic Theology, ed. John Webster, Kathryn Tanner, and Ian Torrance (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), pp. 35–53. For a review of recent discussions of the Trinity by theologians and philosophers of religion, see Stephen T. Davis, Daniel Kendall, and Gerald O’Collins, eds., The Trinity: An Interdisciplinary Symposium on The Trinity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999); Thomas McCall and Michael C. Rea, eds. Philosophical and Theological Essays on the Trinity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009); Thomas H. McCall, Which Trinity? Whose Monotheism? Philosophical and Systematic Theologians on the Metaphysics of Trinitarian Theology (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2010); Scott R. Swain, The Trinity: An Introduction, Short Studies in Systematic Theology (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2020); and Matthew Barrett, Simply Trinity: The Unmanipulated Father, Son, and Spirit (Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 2021).

[3] As argued earlier in John Jefferson Davis, review of Who’s Tampering with the Trinity? by Millard J. Erickson, Priscilla Papers 25.4 (2011): 28–30.

[4] This paper builds upon and develops two of my previous articles on the Trinity: “Lessons from the Proton for Trinitarian Theology?” Science and Christian Belief 34.2 (2022): 130–41; and “Updating Cappadocian Answers to the One and Threeness Problem of the Trinity: With Analogies from Modern Physics,” Doon Theological Journal 19.1–2 (2022): 5–25

[5] For the following section, see John Jefferson Davis, “Lessons from the Proton,” 131–33. For a helpful overview of issues raised by the use of analogy in theology see Philip A. Rolnick, “Analogy,” in The Cambridge Dictionary of Christian Theology, ed. Ian A. McFarland, David A. S. Ferguson, Karen Kilby, and Ian R. Torrance (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 10–12, and David B. Burrell, Analogy and Philosophical Language (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1974). Also by Burrell, on analogy in Aquinas, see Aquinas: God and Action (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1979), 55–77, “Analogical Predication.”

[6] Augustine, De Trinitate 6.12, cited in Andrew Robinson, God in the World of Signs (Leiden: Brill, 2010), “Vestiges of the Trinity in Creation,” 259. Augustine’s notion of the vestigium trinitatis is affirmed by Aquinas in Summa Theologiae 1a, 45, 7.

[7] Augustine, De Trinitate 6.5; 14.7; 15.17.

[8] Tertullian, Against Praxeas 9 (ANF 3:602–3).

[9] Gregory of Nazianzus, Fifth Theological Oration 14, in Christology of the Later Fathers, ed. Edward Rochie Hardy, LCC 3 (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1954), 202.

[10] Cited in Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics, ed. G. W. Bromiley and T. F. Torrance (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1936, 1975), I.1:336. Barth presents an extensive (though not appreciative) survey of the history of the Vestigium Trinitatis on pp. 333–47.

[11] For a comprehensive review of the history of interpretation of the term θειότης (Rom 1:20) and the similar term (θεότης) in Colossians 2:9, see the classic article of H. S. Nash, “theioteis—theoteis, Rom 1.20; Col 2:9,” JBL 18 (1899): 1–34. Nash concludes that the two terms are basically synonyms, without a clear distinction between “divinity” (Rom 1:20) and “deity” (Col 2:9) as came to be commonly supposed in the history of interpretation.

[12] Romans 1:19–20 is a statement about God’s general revelation in nature, not a statement of “natural theology” as such. On general revelation, see Bruce A. Demarest, General Revelation: Historical Views and Contemporary Issues (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1982).

[13] The doctrine of God’s general revelation in nature is not limited to these specific texts. More broadly, the nature of God is revealed in Scripture through many images and metaphors. God is described in terms of light, water, wind, fire, bread, shepherd, father, and so on. These images from the created order provide further foundation for the knowledge of God by analogy—the insight that things of the created order communicate (partial) truths of God with both elements of similarity and difference.

[14] Augustine, De Trinitate 5.9.

[15] For the following section on the Nested Counting Rule, see Davis, “Updating Cappadocian Answers,” 14–17.

[16] For further discussion of the Nested Counting Rule as applied to the Hypostatic Union, see John Jefferson Davis, “Chalcedon Contemporized: Jesus as Fully Person—without Nestorianism; the Hypostatic Union as Nested Relation,” Philosophia Christi 22 (2020): 269–84, esp. 277–83.

[17] For this section, see Davis, “Updating Cappadocian Answers,” 10. For a concise overview of the history of the discipline of mereology, see Achille Varzi, “Mereology,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (2016), https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/mereology/. For the medieval period, see Andrew Arlig, “Medieval Mereology,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (2023), https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/mereology-medieval/. For modern developments, see Peter Simons, Parts: A Study in Ontology (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1987), and N. Rescher and P. Oppenheim, “Logical Analysis of Gestalt Concepts,” British Journal for the Philosophy of Science 6 (1955): 89–106.

[18] Augustine, De Trinitate 6.10.12.

[19] Hilary, De Trinitate 3.1.

[20] John of Damascus, De Fide Orthodoxa 1.14.11–18.

[21] On the predicative use of the copulative, compare John 1:1: “in the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” Here θεός is used in two distinct senses. The Word was with God—with God the Father; and the Word was “God”—i.e., of the nature of God. On John 1:1 see Daniel B. Wallace, Greek Grammar Beyond the Basics: An Exegetical Syntax of the New Testament (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1996), 269, on a qualitative or predicative sense of θεός: “The idea … here is that the Word had all the attributes or qualities that ‘the God’ of 1:1b had … he shared the essence of the Father, though they differed in person.”

[22] This point has been very helpfully stated by William Hasker: “Each Person is wholly God, but each Person is not the Whole of God,” in Metaphysics and the Tri-Personal God, Oxford Studies in Analytic Theology (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 250, italics original.

[23] For the following section, see my earlier article, “Lessons from the Proton, 130–41.

[24] For the history of the discovery of quarks and their physical properties, see Timothy Paul Smith, Hidden Worlds: Hunting for Quarks in Ordinary Matter (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003), 90–108, “Particle Taxonomy,” and 131–47, “Three Quarks Plus”; and Frank Close, The New Cosmic Onion: Quarks and the Nature of the Universe (New York: Taylor and Francis, 2007), 75–106. See also James Dodd and Ben Gripaios, The Ideas of Particle Physics, 4th ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020), 143–64, “Quantum Chromodynamics—the Theory of Quarks.”

[25] Gell-Mann gives his account of his naming of the quark in Murray Gell-Mann, The Quark and the Jaguar: Adventures in the Simple and the Complex (New York: W. H. Freeman, 1994), 180–81.

[26] A. Romer, “Proton or Prouton? Rutherford and the Depths of the Atom,” American Journal of Physics 65.8 (1997): 707–16.

[27] On the epistemic issues raised by complementarity in quantum physics, see Jan Faye, “Copenhagen Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (2019), §4 (“Complementarity”), https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/qm-copenhagen/. For the scientific and historical background, see R. Eisberg and R. Resnick, Quantum Physics of Atoms, Molecules, Solids Nuclei, and Particles 2nd ed. (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1985), 59–60.

John Jefferson Davis

John Jefferson Davis is senior professor of systematic theology and Christian ethics at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary in Hamilton, Massachusetts, and a winner of the Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences award for excellence in the teaching of science and religion.

Other Articles in this Issue

Menzies responds to Tupamahu’s post-colonial critique of the Pentecostal reading of Acts and the missionary enterprise...

The Lamblike Servant: The Function of John’s Use of the OT for Understanding Jesus’s Death

by David V. ChristensenIn this article, I argue that John provides a window into the mechanics of how Jesus’s death saves, and this window is his use of the OT...

Geerhardus Vos: His Biblical-Theological Method and a Biblical Theology of Gender

by Andreas J. KöstenbergerThis article seeks to construct a biblical theology of gender based on Geerhardus Vos’s magisterial Biblical Theology...

A well-known Christian intellectual and cultural commentator, John Stonestreet, has often publicly spoken of the need for Christians to develop a theology of “getting fired...

Postmillennialism had been pronounced dead when R...