Not too often do you get 25 or so leaders together, even on the Web, to talk about the future of their movement. Readers of this blog may have seen the collection of essays assembled last week at Patheos by leaders of evangelicalism reflecting on its health and future. Collin Hansen, Justin Taylor, and Kevin DeYoung wrote on The Evangelical Reformed Movement. Going unnoticed to many, Patheos did the very same thing with mainline Protestantism the week before. Since the 1960s historians and sociologists have catalogued the mainline’s steady decline. Many churches now live solely on their endowments. How then, do the leaders of such a declining group face the future?

The responses vary, which is no surprise since mainliners have little-to-no confessionalism at their core. But there were a few things that characterized them collectively. Every essay recognized the reality of shrinking numbers and the disappearance of youth, but not a few predicted a hopeful future. The optimistic ones claim that mainliners are best equipped to adapt to society’s spiritual climate of pluralism. And Americans younger than 35 have already made their minds up about homosexuality, concludes Lisa Larges, an advocate for homosexuals in the PC(USA). “This generation supports equal rights and ‘equal rites.’”

Creative progressive congregations are the wild flowers amid institutional ruin, according to Jim Burklo, associate dean of religious life at the University of Southern California. Hopeful mainline churches are places where “new music and liturgy are being created, leaving supernatural theism and biblical literalism behind, and embracing anew the long tradition of mystical and experiential faith,” he writes (emphasis mine). Yet this future hope is never articulated as religious dominance, writes Anne Howard of the Beatitude Society, since progressive Christians desire to “neither provide the ‘right answer’ nor to privilege Christianity over any other religion but rather to join with others to serve the common good.” Most essays urge the progressive to progress, question everything, and focus on youth.

You won’t find in any of the essays an appeal for evangelical renewal. In fact, many argue that the residue of conservatism in mainline denominations caused debates that repelled disinterested congregants. While many authors recognize that evangelicals enjoy larger numbers and greater media exposure, some foresee the end of their dominance, “since dominance creates bureaucracy, and bureaucracies tend to grow stale over time,” writes James Wellman, a professor at the University of Washington.

Still, it is remarkable, if not surprising, that no one recommends beefing up orthodoxy or emphasizing a sin-forgiving gospel. Nor do any relate the decline in numbers to theologically liberal conclusions.

Rodney Stark, distinguished professor of the social sciences at Baylor University, when asked about the cause of the mainline’s decline, responded at Patheos:

If you look at the leading lights in American Protestantism in the early 20th century, the famous people didn’t believe in the divinity of Jesus. They were very shaky about the existence of God. They always talked about God, but when you got down into their books and pushed, God was some kind of social value. There wasn’t a one of them who believed in a God who could hear prayers.

Well, they may be right about God. But that doesn’t make for a strong church. As a matter of fact, it doesn’t make for much of anything. If God doesn’t hear or care, if God is not in fact an intelligent entity of some kind, if God is only an ideal, then church is an irrelevancy.

These essays not so subtly remind us that the difference between evangelicals and liberal Protestants is not marginal. Rather, as John Gresham Machen clarified in his book Christianity and Liberalism, they practice two different religions. You don’t need the Bible to make the conclusions progressive Christians have reached. In fact, you need to dismiss it. When mainline Protestants abandon the biblical gospel of the forgiveness of sins through the substitutionary Savior, Jesus Christ, they have abandoned any real hope. In their quest for relevance, they have found irrelevance. Millions who have abandoned the mainline testify to this sad fact, even if the remaining leaders don’t get it. May God protect evangelicals from repeating these mistakes, so that we might never sideline the gospel of first importance.

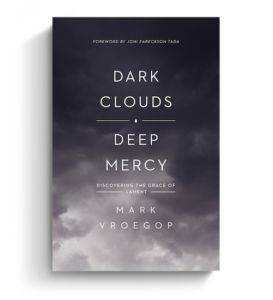

In a season of sorrow? This FREE eBook will guide you in biblical lament

Lament is how we bring our sorrow to God—but it is a neglected dimension of the Christian life for many Christians today. We need to recover the practice of honest spiritual struggle that gives us permission to vocalize our pain and wrestle with our sorrow.

Lament is how we bring our sorrow to God—but it is a neglected dimension of the Christian life for many Christians today. We need to recover the practice of honest spiritual struggle that gives us permission to vocalize our pain and wrestle with our sorrow.

In Dark Clouds, Deep Mercy, pastor and TGC Council member Mark Vroegop explores how the Bible—through the psalms of lament and the book of Lamentations—gives voice to our pain. He invites readers to grieve, struggle, and tap into the rich reservoir of grace and mercy God offers in the darkest moments of our lives.

Click on the link below to get instant access to your FREE Dark Clouds, Deep Mercy eBook now!